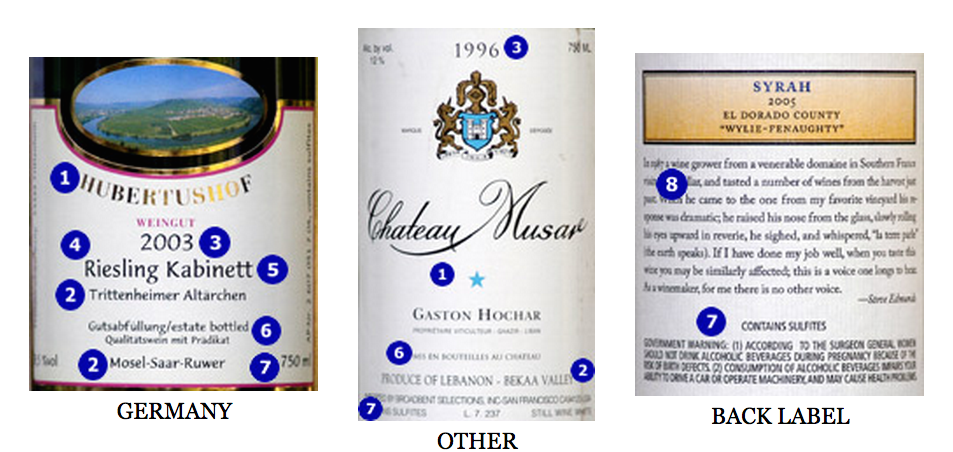

For the new wine lover, few things about fine wine are more daunting than the wine-bottle label. All that small print! All those foreign words and terms! But bear in mind that information brings knowledge, and lots of print conveys lots of information. Learn to decode the label, and you’ve armed yourself with the tools you need to be a savvy consumer.

Take a look at the label images above, then follow the red numbers from each label to the related numbers in the text for a quick explanation of every label line. Even though these labels represent five countries with five different sets of labeling regulations, you’ll soon see that they all provide the same general information, with only relatively minor differences in format and content.

1. Wine maker or winery: The company or firm that made the wine or, in some cases, the wine’s trademark name.

2. Appellation: The country or region where the grapes for this wine were grown. This may be as broad as “California” or as narrow as a specific vineyard like “Trittenheimer Altärchen.” Note, however, that the California wine pictured here lists a more narrow appellation (“El Dorado County”) and takes advantage of the option to denote its specific vineyard source (“Wylie-Fenaughty”) as well. The German wine also mentions its region (“Mosel-Saar-Ruwer”). In most countries, wine-growing regions (“appellations”) are defined by law, and wines made in these regions will carry legal language on the label such as “Appellation Controlée” in France or “Denominazione della Origine Contrallata (DOC)” in Italy. Most regulations allow up to 15 percent of the wine to be made from grapes grown outside the area.

3. Vintage: This is the year in which the grapes were harvested, not the year in which the wine was bottled, which for some wines may be years later. Note that some countries add the local word for “vintage” to the label: “Cosecha” in Spain, “Vendemmia” in Italian. (Most national wine laws require that at least 85 percent of the wine be harvested in the year of vintage; up to 15 percent may be blended in from other years.)

4. Variety: The specific kind of grapes from which the wine was made. Not all wines disclose varietal content. Most French and Italian wines do not do so, for example, because the wine laws require the wines of each region be made from traditional varieties: Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Petite Verdot and Malbec in Bordeaux, for example; Sangiovese and others in the case of Chianti, and the indigenous grapes Obidiah and Merwah in the offbeat Lebanese white wine from Chateau Musar pictured under “Other.” Most countries allow the use of some non-varietal grapes in the blend. In most states of the U.S., for example, only 75 percent of the wine’s content must be of the named varietal. In Europe and Australia, the rule is usually 85 percent.

5. Ripeness: In a tradition known primarily in Germany and, in somewhat different form, Austria, some wines use special terminology to reflect the ripeness of the grapes and the quality of the finished wine. The German wine pictured, for instance, is a “Kabinett,” the lowest ripeness level in “Qualitätswein mit Prädikat,” the highest quality level. For more information on the German system, read John Trombley’s excellent article, Knowing the German Quality System for Wines. Some German wine labels will also show “Trocken” (“Dry”) or “Halbtrocken” (“Half Dry”) to denote wines vinified to less natural sweetness.

6. Estate bottling and winery information: If the wine is “estate bottled” (made from grapes grown and harvested in the winery’s own vineyards), this will be disclosed with language on the label such as the French “Mise en bouteille(s) au Chateau;” the German “Gutsabfüllung“; or the English “estate bottled” or “grown, produced and bottled.”

7. Other required information: This may vary widely depending on national regulations. German wines, for example, carry an “Amptliche Prüfungs Nummer (AP Number),” the serial number it received during official testing (barely visible on the right in the pictured label). French wines may carry their ranking from traditional classifications (such as “Grand Cru” or “Premier Cru” on qualifying Burgundies). The back labels of wines sold in the U.S. are typically decked out with required consumer warnings such as the notorious “Surgeon General’s Warning” and notices that the wines contain sulfites. Wine labels also carry small print disclosing the wine’s approximate alcoholic content and the size of the bottle, as highlighted on several of the labels photos. Imported wines in the U.S. normally bear the name and other information about the company that imported the wine.

8. Optional information: Additional information that may range from winemaker’s notes or detailed analytical and tasting information to advertising hype are often featured on labels, especially the back label. Not to mention the ubiquitous UPC bar code!

See? That wasn’t so bad, was it? I hope this brief tutorial has made you more comfortable with your wine shopping. But if you ever run into a label term that you can’t figure out, or find a quirky label that doesn’t fit these general rules, please feel free to get in touch!

Since you are in to wine labelling, you might also find the Seareach web site a good place to visit. They use original Pantone approved inks when they produce their labels. Seareach produce asset tags with barcodes to help with tracking of your wine bottles. To stop bottles being opened without prior notification, they provide tamper-evident security labels. If you try and tamper with a screw top or cork, it becomes instantly visible – which is good for security and your own peace of mind. You can find more information on security printing through the PIRA website in the UK.